The life and times of Papa

Papa’s been around. It was about 30 years ago that I set Papa in motion, using a varied concoction of cooked grains, a touch of honey and a bit of Breton sea salt. It was called a ‘honey salt levian’, and it was one technique I had been experimenting with for making my (at the time) somewhat dense little wheaty loaves.

Papa, for the uninitiated, is the name my kids gave to my sourdough starter. He was named pretty late in the piece - for the first 20 years or so, Papa was nameless; an anonymous organic Frankenstein who was only partially under control.

The honey salt fermentation technique was coming to me via Demeter Bakery at Glebe. I had been given this very rough set of hand typed notes, translated from German. The bakers at Demeter had said they were not using this technique, as their method was a somewhat more sophisticated one, using specially prepared crystals from Germany. So I got to try it out, a kind of hand-me-down technique, with Simon Brownbridge and Jurek Kostrewzki, who would later become my first business partners in our very first ‘legal’ bakery, ‘Heaven’s Leaven’. We were all mucking around with our breadmaking individually, making earthy little bricks which we thought were pretty yummy - the sort of things only a mother could love (with the benefit of hindsight).

At that time, Demeter were the only naturally fermented bread being made in Sydney - at least bread that was widely available, anyway. The bread from Demeter was positively virtuous. You could sense the wheat, the earth, the sky, and all the elements just emanating from the bread. It was ‘life force central’.

So I was kind of reinventing the honey salt leaven in my kitchen in Waverly. I was using porridges, or cooked grains, a different grain for each day of the week, in fact. I figured that to attract whatever it was that made the leaven ferment, it should be fed from a representation of all the grains. There was very little written about the subject - there was no internet; just a few books. So people like me just made it up as we went along.

The Frankenstein tag was apt; on one occasion, my carefully tended starter exploded like a bottle of champagne all over the roof and walls of our little flat. I remember watching it all happen; I also remember spending a whole day climbing up on top of the cupboards scraping starter off everything in sight - the roof, the walls, and everything else that was positioned on top of the cupboard alongside my starter jars.

My very own baptism by flour and water.

Eventually I built this ferment into a wholewheat liquid starter, with a bit of honey and sea salt. The addition of these things kept the leaven neutral in flavour, while still helping with a good, consistent rise.

It was lovely, fulsome bread, and at the time it was as good as there was. Papa was earning his keep. We were baking dozens of loaves at a time.

Then I tasted some of Roland Dallas’ ‘gourmet’ breads. Now this guy was a baker - the breads were a treat, made by a ‘proper baker’. Some of them were naturally leavened, some yeasted - but all were super tasty, and right outside the mold of what bread was supposed to be.

At the same time, Natural Tucker Bakery was doing great business in Melbourne, followed by Firebrand; in NSW little bakeries like Blackheath Bakery were popping up around the place, though social media wasn’t around to spread the word, so you just had to discover stuff through travelling and eating.

Papa, by this time, had grown quite a bit, and had moved house twice to accommodate bigger kitchens, so I could bake more bread. Our first proper bakery became a renovated chemist shop in Clovelly. This is where Papa’s life as a daily bread worker began.

In time, Papa and I outgrew our Clovelly setup. I wanted to make some of this very rustic, very crusty sourdough which I had been discovering little by little, while Simon and Jurek preferred to stick to the honey salt concept.

I packed what I needed into the back of a truck and headed up to the Blue Mountains.

Leura.

I purchased a tiny little cafe in Leura, converted it into a bakery, and Papa morphed into a liquid starter, sans honey and salt. He was now a wholewheat ferment, fed entirely on stone milled wheat flour. Leura was still a sleepy little Blue Mountains village, and wasn’t prepared for my onslaught of alternative bread. To garner a bit more interest in my bread, I altered Papa’s diet to become less wholewheat and more white flour. This gave the bread a more ‘common’ texture - not so grainy. I thought it was more acceptable to the local palette - which was, especially at the time, unaccustomed to these grainy, flavoursome loaves. Australians then, and now, are big fans of ‘white squares’. You know, flavourless square slices which fit neatly in the toaster, and are uniform everywhere you go, despite being made by a multitude of bakeries the country over.

Despite bringing Papa to a diet of white flour, the bread was still pretty dense. People loved it, but most of the fans of my bread were weekend sightseers from Sydney - hungry for something resembling French or European sourdough. The locals came mainly for the coffee - a few intrepid souls became hooked on my grainy loaves, but generally they preferred the white squares from down the road at the local bakery. I decided to lighten my bread using minute amounts of fresh yeast in the dough (never in the starter!) and called this ‘semi leaven’. It was quite light, and yet still flavoursome. Gradually, the locals were won over, and my loaves, both pure sourdough and semi leaven, were embraced.

Papa continued to grow, as demand for the bread grew. We slowly observed Leura as it became a tourist hotspot, and each month the production numbers got larger. Eventually I started sending my loaves back to Sydney. After a year or two of this, the tiny shop in Leura was bursting at the seams with bread to feed the masses in the big smoke down the road. And Papa was occupying more space as well.

We set up a factory sized space in Nth Katoomba to supply Sydney and our own shop in Leura, just down the road. Papa was occupying a 60ltr tub, and needed a feed every day. This involved emptying his daily remains (after production) into our mixer, adding flour and water, mixing, and then putting this back into the tub, where Papa would ripen and be ready for use the next day. It was very labour intensive, but we were making a lot of bread each day by this stage.

In my zeal to streamline things, I bought a large stainless steel urn which had a hollow sleeve around it. This sleeve could be filled with either hot or cold water, allowing the starter to be temperature controlled. I also purchased an industrial scale paint stirrer, which fitted into the top of the urn. I thought it was a really good setup, however after a week strange things started to happen. The bread coming out of the oven looked entirely normal, but when it was cut open, it would be liquid inside. I was flummoxed. I got on the phone and talked to as many experts as I could (there were none, but I knew a few old school bakers so that became my knowledge base).

Nth Katoomba

There was no internet at this stage. It was all very confusing (still is, even with the endless resource base of global bakers!). In the end, I ditched all but a couple of cups of starter, and rebuilt it by doubling the volume of the remaining starter every few hours, keeping it warm the whole time. I returned the starter to its original plastic tub, as I figured the only thing that had changed was the container. After 2 days I had the volume back to where it was, and the bread was no longer liquefying.

I assumed that the stainless steel tub was the problem - though I had no idea why. Research a number of years later has shown that stainless steel is used for lots of fermentation processes - beer, wine and starter being commonly kept in stainless. Nonetheless, a return to a plastic tub solved the problem. I purchased a larger tub, and cut a hole in the lid, poking my industrial scale paint stirrer in it. This meant that I could now feed the starter with a bag of flour and a bucket of water each day, turn on the strirrer, and leave the whole thing to mix inside the cool room, ready for use the following day. No more cleaning mixers.

I now believe the problem wasn’t the stainless; it was cleaning. I bought the stainless tub from a mate who had an organic shampoo and conditioner factory down the road. When I took delivery, I cleaned it fairly thoroughly, but it’s possible that traces of emulsifiers and binders were left in the tub, causing the delicate microbial balance in the starter to be disturbed.

So Papa has recovered from a near death experience.

That bakery grew and grew, until it was processing something like 5 tonnes of flour a week. At that time, there were no other sourdough bakeries in Sydney, so we had the whole place to ourselves. Eventually, though, more players entered the space, and we found ourselves competeing with Sydney based manufacturers. I hung on to the business for too long. My competitors had the edge, as they were local. I was forced to wind things up some years later. I dismantled things, and took my family to Newcastle, where there was a good sized population, schools for my kids, and no sourdough bakeries.

Community Supported Bakery V1

Five years after moving to Newcastle, I started an early version of what has become my Community Supported Bakery, and Papa’s first run in a commercial context as a Desem starter began. During this time I was able to perfect the technique from a production perspective - and found that it assisted greatly with biological development in dough. I had returned to hand mixing dough, and I found that a nice long preferment made hand mixing much easier, as a great deal of the gluten development occurs naturally in the sponge, or ‘young levain’.

Crossing the country with Papa

My CSB (Community Supported Bakery) has had a few relocations now, and Papa has been involved with every one, adapting to local conditions each time. About a year ago, while I was waiting for the latest space to be rebuilt (in a big old dairy shed on a working cattle farm) I decided to pack Papa into a trailer I repurposed to become a tiny off grid bakery, and head across Australia, teaching and writing. I gave about 13 workshops along the way, crossing the Nullabor with Papa, my dog Pippa, and Mishka the cat. Papa survived the trip with a bare minimum of mod cons for the first time in his life. I had no proper refrigeration on the trailler, so Papa had to be maintained often along the way. He developed a rather musty smell as a result, adding enormously to his character.

Now the old dairy shed has been fully converted, and I’ve been baking here for about 6 months. It’s an absolute treat to have all the mod cons again, like refrigeration and a mixer. Papa is deeply happy - though he still smells a bit, well, complex. Old dudes are allowed to.

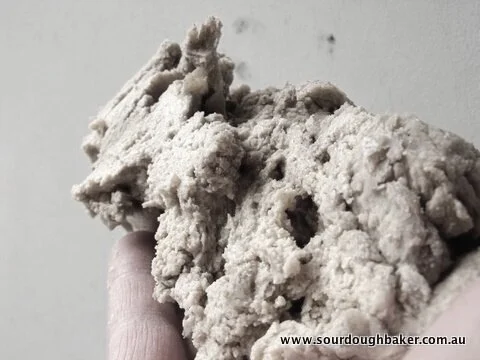

Currently Papa occupies a 20 litre tub. I only need to feed him every couple of weeks. I use 200g of Papa to make each dough - about 25 loaves. I keep extra because Papa makes lots of babies, which are sent to the farthest reaches of the country. As a 30 year old starter, he gets his DNA out there on a daily basis, helping people get their sourdough journey underway.

I use Papa at about 1% of the total dough weight (or 1.6% if you calculate using baker’s percentages) - stronger than fresh yeast - though my technique is also much, much slower. The fermentation cycle for my bread is currently about 72 hours from start to finish. If I were to shorten this, I suppose I would use 2%.

Papa’s been a mate of mine now for 30 years, give or take. He’s a powerful piece of microbiology, and he has done more than his fair share of the heavy lifting in every one of my bakeries. We’ve had a few adventures together, and while he isn’t all that talkative, I know his story finds its way into every loaf he has had a part in creating.